Since the late 1980s through the end of 2021, for a long 30+ years, almost without exception, policy was ubiquitously supportive of markets. If the markets or economy got into trouble, policy would come to the rescue by either cutting rates, injecting liquidity into the system, increasing fiscal spending, making direct asset purchases, changing reserve requirements, etc. The financial crisis saw TARP and a slew of supportive policies, Covid saw unprecedented monetary and fiscal policies. Even the tech bubble bursting, which barely impacted the broader economy, was soothed by policy that cut rates and eased rules around home ownership. Perhaps they soothed one bubble bursting by creating another, but intentions were good.

Let’s focus just on the Fed, even though this recent trend in policy spans many channels and countries. The Fed came to the rescue of markets reliably from ’87 to ’21 (chart above with the little green check marks). But before the late ‘80s and more recently, it wasn’t as supportive (little red check marks).

Perhaps we could argue that low/falling inflation allowed the Fed to be super supportive without consequences. In the 1970s and since 2021, inflation remained elevated, limiting the central bank’s rate-cutting ability. But it isn’t just the Fed’s monetary policy. Policy everywhere, beyond central banks and in most countries, has been very supportive of markets and the economy during this late ‘80s to 2021 period.

Supporting markets and the economy worked well, and it really resonates with voters. Higher markets make people happy, right? For some reason, that’s not so anymore, as voters are clearly unhappy with established parties and continue to vote for material change. Income disparity, lack of opportunities, costs of living and home ownership, trade injustices, etc. – whether these are real or just perceived, the global trend is voting in politicians to tackle these other issues.

So policy change is afoot in the 2020s, with the downside that policy uncertainty is higher now and relying on policy to save markets may be more tenuous. This isn’t a bad thing; bigger problems are starting to be addressed these days globally, which is likely good for society.

The challenge is that markets would prefer no change unless they need help. But the world has some big challenges, and these could use addressing. Some may be positive for markets, like an effort to improve productivity or growth. Some are not, like changing trade/tax rules.

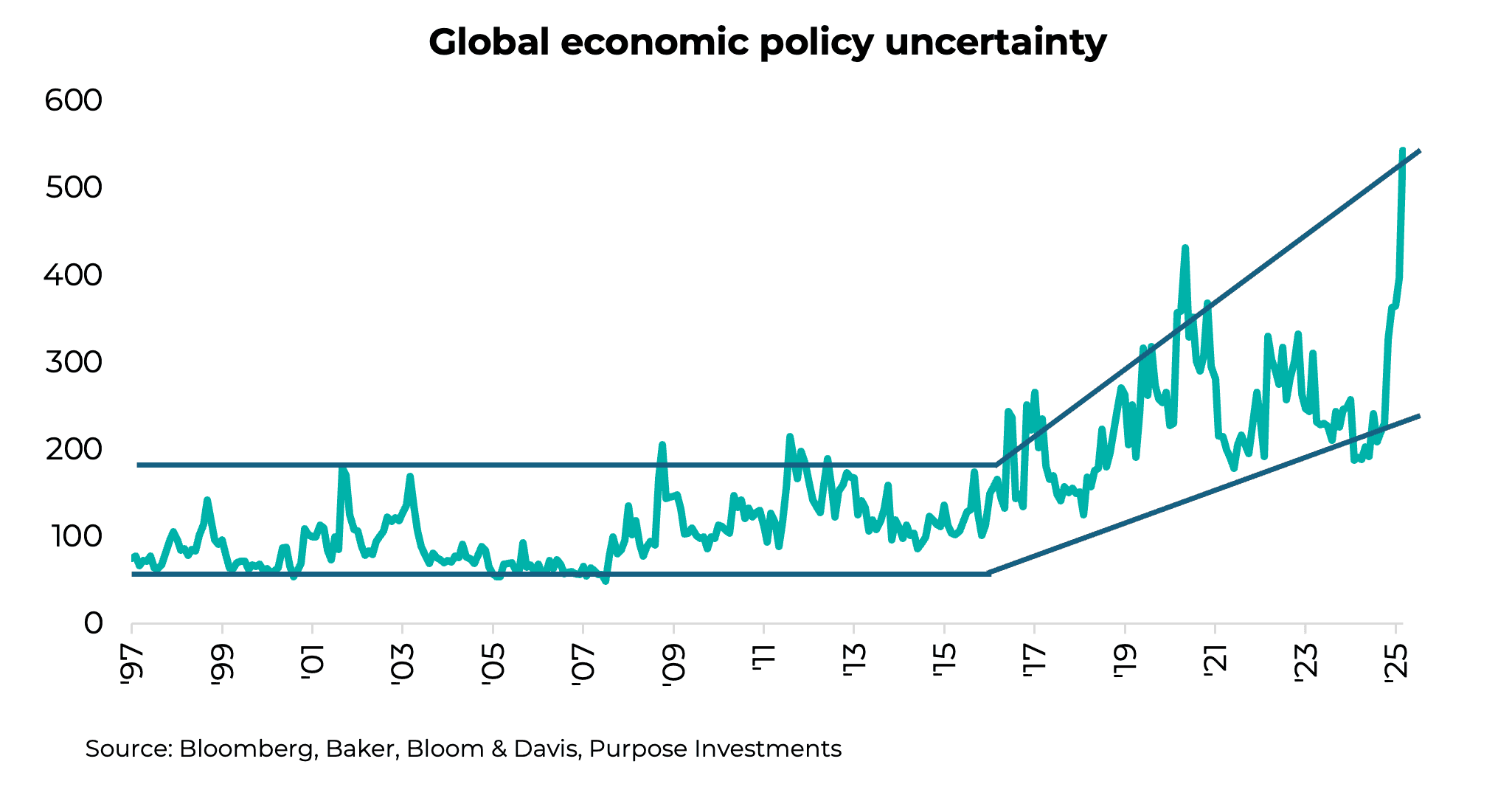

This isn’t just because we have a new president, this rising policy uncertainty has been rising for a while. The challenge is that we are now likely going to see more policy corrections, like the one earlier this year. A change of policy, whether well-founded or not, creates a spike of uncertainty in the markets.

The good news, historically, is that policy or event-driven corrections are short-lived. Clearly, this one was, with the one caveat that a policy or event correction can cause a growth slowdown, which would morph a policy correction into a more traditional economic weakness variety. Time will tell if this is in the cards in the coming months.

If we’re in an era of higher policy uncertainty, this would likely increase the frequency of policy-induced corrections. Every correction is different in duration, speed, and root cause. Most are familiar with an economic slowdown correction: The economy starts to slow, earnings come under pressure, and markets react negatively. This variety of correction was dominant over the previous 30 years.

But we are now experiencing more unique corrections, caused by exogenous shocks like Covid (2020), inflation (2022) or policy (2025). Given higher inflation and a more uncertain policy environment, these more unique corrections may be more prevalent in the 2020s than the plain vanilla variant.

The challenge from a portfolio construction perspective is that these more unique corrections may require a different strategy. For a plain vanilla economic slowdown correction, the traditional portfolio diversifiers like bonds and U.S. dollar exposure work really well. For the other types, these diversifiers often don’t work as well, while other diversifiers work really well. The table below highlights the challenge by looking at what helped, hurt or was kinda in the middle from a defence diversification perspective over each correction.

Even though Covid was an exogenous shock, traditional core diversifiers, including bonds and U.S. dollar exposure, helped the most. With inflation in 2022, the TSX did relatively well among equities thanks to resources exposure; gold helped a bit, while the U.S. dollar shone bright. And in this most recent policy correction, the TSX, international, and bonds maybe helped a bit, while the U.S. dollar sucked and gold came to the rescue.

The takeaway for portfolio construction is that while bonds remain the core defence provider, because slowing economic growth concerns will likely still be the most common correction type, atypical corrections are increasing in frequency, requiring different types of diversifiers. This supports our view that portfolios should have more diversified defence from more international equity exposure, including incrementally more alternative sources from volatility management, momentum or gold.

Additionally, a more tactical approach is needed for periods of weakness. If that involves policy or an exogenous shock is induced, we recommend a quicker buying-the-dip approach. Inflation or economic weakness-driven corrections may require more patience, as these take longer to work their way through market prices. It simply isn’t as easy to diversify as it has been in previous decades, requiring a more thoughtful approach to defence.

Emerging Markets Are Still Worth a Sliver

Instead of “Buy American,” investors are increasingly saying “Bye, America” and looking elsewhere to invest their capital. So far this year, the S&P 500 has rallied back from the brink of a bear market to being flat on the year, while international developed markets are relative winners with the MSCI EAFE index up 17%. Looking beyond the developed nations in the EAFE index, even emerging markets are having a strong year, up around 8% year-to-date.

We increased our allocation to emerging markets in our multi-asset portfolios just over a year ago, a position that has since seen the asset class keep pace with developed markets. However, this headline performance masks significant dispersion at the country level. Over the past year, China has delivered an impressive 20% return, handily outperforming its developed and developing counterparts. In contrast, markets such as India, Taiwan, and South Korea have faced a more challenging environment. India, for its part, is showing signs of recovery and is now positive year-to-date after a significant drawdown from its peak last fall. Among the strongest emerging market performers year-to-date are Brazil (+20%), South Africa (+16%), and China (+14%).

Our positive view on emerging market equities, established after a long period of underperformance, as seen in the chart below, remains intact. The original thesis is underpinned by attractive valuations, an improving earnings outlook, and supportive macroeconomic conditions. We believe we are in the early stages of a long-term cycle of EM strength. While the recent gains are but a small blip on the long-term chart and risks remain, including the trade war and uncertain tariff impacts, we believe the positive fundamentals in the asset class present a compelling counterbalance for portfolios.

Valuations are still attractive

Emerging markets currently offer one of the most attractive valuation propositions in decades relative to developed markets. The EM index trades at approximately 12.5x forward earnings compared to 21.7x for the S&P 500 and 19.3x for developed markets, representing a substantial 35% discount to developed market equities. This discount reached a record earlier this year, but with a still lofty 6.8-point spread between emerging and developed markets, they remain quite attractive from a valuation perspective, providing a significant margin of safety for long-term investors.

The valuation story becomes even more compelling when examining EM value stocks specifically. The MSCI EM Value Index trades at just 9.5 forward price-to-earnings, in line with its 20-year average. In contrast, the MSCI World Value Index trades at 14.8x, two points above its 20-year average. The combination of low valuations and improving fundamental characteristics creates an asymmetric risk-reward profile favouring EM allocations.

With valuations in many countries, such as China, still very depressed, even a modest uptick in sentiment can have a dramatic impact on share prices. Given that U.S. markets are essentially fully valued, markets that can experience both earnings growth and multiple expansion offer an attractive runway to outsized returns.

Earnings growth recovery and momentum

After years of disappointing earnings performance, emerging markets are experiencing a significant earnings revival that should drive future returns. EM earnings per share growth accelerated meaningfully in 2024 and is expected to continue growing strongly in 2025, representing a major shift from the previous ten-year average of just 2%. Earnings growth expectations have slowed for both emerging markets and developed markets, with the growth rates for both staying about the same.

EM relative earnings are historically depressed compared to developed markets, which skews the risk-reward equation in favour of emerging markets. With trade tensions easing and global growth conditions expected to remain supportive, EM relative earnings have significant upside potential over the next six to 12 months, even in scenarios where global growth moderates.

Favourable dollar dynamics

The U.S. dollar is down considerably in 2025, which has led to fears of dollar debasement and foreign investors dumping Treasuries and other U.S. assets (perhaps overblown but a popular narrative these days). While we don’t believe this to be a major cause for concern, our outlook is that a weaker U.S. dollar provides a significant tailwind for emerging market assets.

In the chart below, you can see the strong correlation between EM outperformance and dollar weakness. There is a strong historical inverse correlation, and while the correlation may not be as strong now compared to the past, it should still be a benefit. One of the reasons why the relationship may not be as strong is that the amount of emerging market government and corporate debt denominated in U.S. dollars has shrunk over the years, with an increasing amount denominated in local currency.

This currency dynamic has likely already benefited EM equities, with the dollar index down 10% from its highs. Based on the chart below, it has helped, but the backdrop of a softening U.S. dollar should continue to be a tailwind longer-term.

Final Thoughts

While the U.S. is busy putting up barriers to trade, globally, most trade happens without the U.S. In the current environment, it’s likely that foreign companies would be increasingly willing to look to other markets outside of the U.S. rather than deal with higher tariffs. Emerging markets are in a prime position to benefit, with more trade occurring outside the US.

From a portfolio construction perspective, the gap between EM's share of global GDP (39%) and its weight in the global market cap (26%) suggests a structural underweighting that should correct over time. While there is no hard science to determine an optimal EM allocation, we view a 5% exposure as a good baseline. We’re fully aware of the under-allocation compared to the global market cap weight, but given the tradeoffs between risk and potential return, we view 5% as large enough to make a difference without risking too much.

The convergence of attractive valuations, improving earnings fundamentals, supportive macro conditions, diversification benefits, and structural growth drivers creates a compelling case for maintaining meaningful EM allocations. Recent upgrades from major investment banks reflect growing recognition that the risk-reward equation has shifted in favour of emerging markets after years of underperformance. While volatility will persist, the current environment offers patient investors an opportunity to allocate to EM at valuations that may prove exceptional in hindsight.

Global in Name Only

There are certain phrases in portfolio management that we accept at face value, like “balanced portfolio.” “Global equity” is another one. You would think the title says it all – it sounds like a diversified portfolio with exposure across many regions. But these days, “global equity” often means one thing: The United States. And you might be holding more of it than you think.

It is no secret that the U.S. has dominated the last 10-15 years of equity returns, powered by megacap tech and accretive policy tailwinds along the way. Naturally, that success pulled more capital in, and over time, it’s changed the shape of everything it touches, including the funds meant to look beyond it.

After the global financial crisis, North American global equity managers held just over 40% in U.S. equities, a modest allocation that felt reasonable given the size and influence of the U.S. market. While 40% is still a substantial country weight, it reflects a more balanced global approach. Today, that number has climbed as high as 62% and currently sits around 59%.

This shift has quietly redefined what it means to invest globally. And to be clear, no one’s blaming the managers. Ignoring U.S. dominance over the past decade would’ve been career suicide. The issue isn’t how we got here; it’s whether we’re still comfortable with where we are.

As a result, this has also influenced portfolio construction, often without investors realizing it. You might assume you're underweight in the U.S. or sitting at a neutral position, but once you look under the hood, the picture tells a different story.

A few weeks back, we shared some thoughts on international equities and touched briefly on how global equity managers are positioned, but we felt it was important to bring the conversation back to the portfolio. From our firsthand work with advisors, there’s been a clear and consistent pattern: U.S. equity weights across portfolios are almost always dominant, especially relative to our baseline.

In most cases, there is an awareness that their U.S. allocation is meaningful, but the idea that it might be an overweight doesn’t always register the same way. We're not saying that's wrong, but it's worth knowing, especially if the positioning wasn’t fully intentional.

But here’s the part that is most often missed. That 47% U.S. equity exposure is not just coming from dedicated U.S. mandates. A meaningful portion is coming in through the “global” positions in the portfolio. Across the portfolios we reviewed, the median allocation to global equity funds was 10% of the total portfolio. And within those funds, the median U.S. equity exposure was 65%. That means within the study, for a typical balanced portfolio with a 60% equity allocation, roughly 11% of the equity sleeve ends up in U.S. equities through global funds alone.

It's one of those things that looks harmless on the surface but changes the entire shape of a portfolio. In many cases, that indirect exposure contribution brings the total weight to a level well above what is believed and almost entirely encapsulates the overweight. The global equity funds are meant to diversify regional risk and instead end up reinforcing it.

Within many of these portfolios, global equity funds have become the primary source of international exposure. And it’s easy to see why. They’ve consistently delivered, though let’s be honest, that’s mostly because of their higher U.S. exposure. That relative strength has driven more allocation to global funds, which in turn increases U.S. concentration even further. Over time, the cycle has fed itself, leaving many portfolios with less true international diversification than the labels suggest.

This is not a red flag for everyone. Some are very comfortable with having a higher U.S. equity weight. The idea is to bring this concentration to light and understand what you own. The real risk here is not just overexposure to the U.S., but underexposure to everything else.

We have had a very strong period for international equities so far this year, and for the most part, many portfolios did not feel that supportive benefit amidst the U.S. weakness. If the first half of the year has taught us anything, it’s that diversification is still alive and well.

This is not a call to unwind U.S. exposure or avoid global mandates, although some portfolios may be able to benefit from it. It’s just a reminder that many of the frameworks we rely on were built during a different version of “global,” and we believe the goal should be to introduce a bit more balance. Moving forward, it may be time to revisit what those funds actually hold and how much of your U.S. equity weight is coming from indirect sources. Nothing in portfolio construction is static, but this trend has moved far enough that it deserves another look.

Global equity isn’t broken, but it’s not what it used to be. If true diversification matters, it’s worth asking whether your global exposure is really as global as it claims to be.

Market Cycle & Portfolio Positioning

The market cycle indicators improved decently over the past month. Economic data did get a bit better, looking at the Citi Economic Surprise Index for the U.S. and the GDP Now from the Atlanta Fed. While not an indicator, Q1 US GDP revisions were not so great, with consumer spending showing a deceleration. Perhaps cooling policy uncertainty around tariffs will alleviate; time will tell.

Another potential upside: The yield curve has steepened. This may not be a huge positive, though. There is much talk of longer yields rising because of deficit concerns, and few are citing improving economic activity. The latter is good, the former not so much.

Nonetheless, an improvement is an improvement. We still believe there may be a period of economic growth weakness later this year as the impact of tariff uncertainty bleeds into the data. And given markets have largely recovered; there does appear to be a lot of good news priced in.

After portfolio tilt changes in March and April, we were quieter in May. We’re holding about neutral on equities, under on bonds, and over on diversifiers and cash. The speed of this rebound is impressive, reminding investors that policy-induced corrections are usually quick. But now with TSX and international indexes around all-time highs, and with the S&P only a few points away, markets certainly have gone back to an “optimistic” mood. As contrarians, this does make us a bit nervous.

Final Note

Markets sure have recovered from the April’s uncertainty-driven correction, as a much less dire scenario appears to be forming. But make no mistake: Policy uncertainty is likely here to stay for some time and not just in America.

So far this year, markets went from overly optimistic in the early months that trade policy would not be an issue, to overreacting to the downside and now back to optimism. Policy could flare up again, but we do think the bigger risk is slowing earnings and economic activity, weighed down by such a prolonged period of uncertainty for investors, consumers, governments, and corporations.

2025 sure does look like a year to be opportunistic. We would encourage keeping a diversified defence and dry powder on hand in case this optimism fades in the summer months.

— Craig Basinger, Derek Benedet and Brett Gustafson

Get the latest market insights in your inbox every week.

Sources: Charts are sourced to Bloomberg L. P.

The content of this document is for informational purposes only and is not being provided in the context of an offering of any securities described herein, nor is it a recommendation or solicitation to buy, hold or sell any security. The information is not investment advice, nor is it tailored to the needs or circumstances of any investor. Information contained in this document is not, and under no circumstances is it to be construed as, an offering memorandum, prospectus, advertisement or public offering of securities. No securities commission or similar regulatory authority has reviewed this document, and any representation to the contrary is an offence. Information contained in this document is believed to be accurate and reliable; however, we cannot guarantee that it is complete or current at all times. The information provided is subject to change without notice.

Commissions, trailing commissions, management fees and expenses all may be associated with investment funds. Please read the prospectus before investing. If the securities are purchased or sold on a stock exchange, you may pay more or receive less than the current net asset value. Investment funds are not guaranteed, their values change frequently, and past performance may not be repeated. Certain statements in this document are forward-looking. Forward-looking statements (“FLS”) are statements that are predictive in nature, depend on or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “could,” “expect,” “anticipate,” intend,” “plan,” “believe,” “estimate” or other similar expressions. Statements that look forward in time or include anything other than historical information are subject to risks and uncertainties, and actual results, actions or events could differ materially from those set forth in the FLS. FLS are not guarantees of future performance and are, by their nature, based on numerous assumptions. Although the FLS contained in this document are based upon what Purpose Investments and the portfolio manager believe to be reasonable assumptions, Purpose Investments and the portfolio manager cannot assure that actual results will be consistent with these FLS. The reader is cautioned to consider the FLS carefully and not to place undue reliance on the FLS. Unless required by applicable law, it is not undertaken, and specifically disclaimed, that there is any intention or obligation to update or revise FLS, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.